Home / Decline of Power, Pursuit of Pleasure, Muhammad Shah, 1719-1748

Decline of Power, Pursuit of Pleasure, Muhammad Shah, 1719-1748

In the thirty years that followed the death of the Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707, the Mughal Empire contracted and Delhi became a hotbed of political contention. Political intrigues were rife—three Emperors were murdered; one was, in addition, first blinded with a hot needle; the mother of a third was strangled, and the father of another forced off a precipice on his elephant.

The longest surviving sovereign of the age, the Muhammad Shah II, called Rangila, or Colorful, was not famed for his industry: in the mornings, partridge and elephant fights were laid on for his pleasure; during the evenings, jugglers and mime artists performed, while the Emperor watched, often dressed in a lady’s long tunic (peshwaz) and pearl-embroidered shoes. But while presiding over the decline of Mughal political power, Muhammad Shah also proved to be a discerning patron, employing such master artists as Nidha Mal (active 1735–75) and Chitarman, whose great master-works show vivacious and bucolic scenes of court life, such as Holi celebrations, hunting and hawking, and even the Emperor making love. Again and again the artists of the period return to the idyll of the Mughal pleasure garden, a hint of escapism, perhaps in reaction to the frequently violent reality.

In addition to reestablishing the imperial painting atelier, Muhammad Shah presided over a remarkable cultural and intellectual renaissance. Delhi’s poets and painters increased in fame as fast as her military fortunes diminished. With a confluence of celebrated scholars, theologians, and mystics, and a host of Urdu poets, musicians, dancers, and painters, Delhi society came to be enlivened by a culture of coffee houses and literary salons. Rich and cultured as it was, shorn of its provinces and most of its army, Delhi remained unprotected. In 1739, Nadir Shah, the ruler of Persia, defeated the Mughal army and advanced on Delhi. After nine hundred of his soldiers were killed in a bazaar brawl, Nadir Shah ordered a massacre. At the end of a single day’s slaughter, thousands of Delhi’s citizens lay dead, and the wealth gathered by generations of Mughal emperors was taken away in a caravan of several thousand carts and camels.

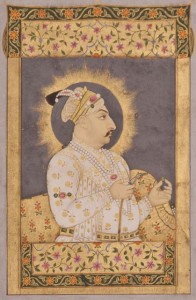

Nidha Mal (active 1735–75) Jharokha portrait of Muhammad Shah holding an emerald and the mouthpiece of a huqqa ca. 1730 Opaque watercolor and gold on paper H. 4 7⁄8 × W. 3 3⁄8 in. (12.4 × 8.5 cm) The San Diego Museum of Art, Edwin Binney 3rd Collection, 1990.376

Exquisitely dressed, bedecked with jewels, and surrounded with lavish textiles, the haloed Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah personifies both imperial demeanor and casual self-indulgence in this window (jharokha) portrait. Holding a huqqa snake in his right hand, and an emerald in the other, the emperor is in his middle years, his increasing girth, carefully documented here by one of the premier court artists, Nidha Mal. Muhammad Shah’s arched eyebrow and salubrious persona characterize the culture of extreme refinement that he patronized, where courtly pleasures held a dominant sway in the emperor’s daily life. In the eighteenth century the idea of a royal window portrait with the huqqa as a royal accessory, acquired much favor across north India, especially in the neighboring Rajput courts.

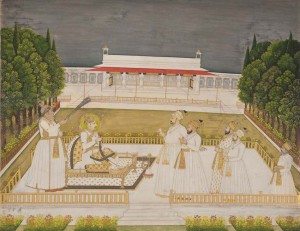

Nidha Mal (active 1735–75) Muhammad Shah enthroned on a terrace at night with his officers ca. 1735 Opaque watercolor and gold on paper H. 12 15⁄16 × W. 16 5⁄8 in. (32.8 × 42.3 cm) The San Diego Museum of Art, Edwin Binney 3rd Collection, 1990.378

In this work, the Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah, holding a huqqa pipe, sits on the open terrace in the royal garden at the Delhi palace, engaged in a conference with his inner circle of ministers. Nidha Mal, whose name is neatly signed near the pierced balustrade to the left, creates a somber mood in this court scene (darbar) by using a tightly controlled geometrical layout emanating from a single point perspective with a white marble palace pavilion at the top of the picture plane. In a tense conversation, probably centering on Roshan ud-Daula, a wealthy intriguer dressed in a printed jama, the emperor listens to his chief paymaster (mir bakshi) Khan Dauran, who is pointing an accusatory finger at the intriguer. Muhammad Shah is fanned by the elder Sadat Khan Burhan ul-Mulk, governor of Awadh, who holds a chauri, while his other ministers and a Rajput lawyer in an unadorned turban (vakil ) look on.

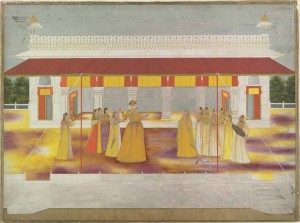

Bhupal Singh (active ca. 1735) Muhammad Shah celebrating Holi ca. 1737 Opaque watercolor and gold H. 13 3⁄8 × W. 18 1⁄8 in. (34 × 45.9 cm) Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, MS Douce Or. b. 3, no. 22

In this vibrant depiction of courtly pleasure, Bhupal Singh has captured Muhammad Shah amidst a riot of color celebrating the semi-religious festival of Holi that marks the advent of spring. The splash of yellow and purple color on the ground surrounding the single story marble palace pavilion indicates that much of the playful skirmish and frolic, resulting from the exchange of dry and wet colors associated with Holi, has just taken place. The emperor stands poised to apply color to Gulab Bai, a prominent courtesan of the Delhi court. Dressed in a floor length jama, his eyes elongated with kohl (surma), Muhammad Shah cuts a rather dandy-like figure, appearing as an embodiment of his sobriquet, Rangila, or Merrymaker. The artist develops the compositional characteristics developed by the painter Chitarman at Muhammad Shah’s court, creating a geometrical frame for the picture using the white vertical columns of the palace pavilion and the horizontal tier of the flat roof adorned with a red canopy.

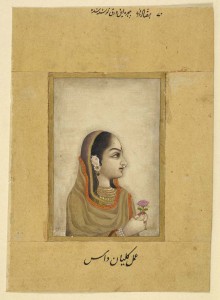

Kalyan Das (active mid-18th century) Portrait of a lady holding a rose ca. 1740 Opaque watercolor and gold on paper Image: H. 3 3⁄4 × W. 2 1⁄2 in. (9.5 × 6.4 cm) Page: H. 6 3⁄4 × W. 4 13⁄16 in. (17.1 × 12.3 cm) British Library, J.60,22

This is a delicately rendered half-length portrait of a lady by Muhammad Shah’s court artist, Kalyan Das, whose signature is inscribed below. Window portraits of beauties had been fashionable in Mughal art since the seventeenth century, yet the figures remain enigmatic, since named portraits of women in Indian painting are few. A number of Delhi painters created idealized models of women characterized by their aquiline features, ornaments, and near transparent clothing often accompanied with verse praising the beauty of a lover. Here, the lady’s jewelled, hennatipped fingers hold a pink rose as she glances with a half-smile into the distance. The red forehead mark (bindi) was worn by Hindu women.

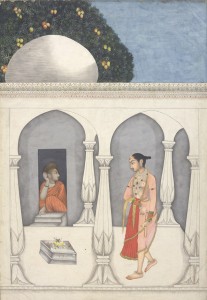

Muhammad Faqirullah Khan (active 1720–70) A lady visiting a Saivite shrine ca. 1750 Opaque watercolor on paper Image: H. 9 3⁄4 × W. 6 13⁄16 in. (24.8 × 17.3 cm) Page: H. 15 11⁄16 × W. 11 1⁄16 in. (39.8 × 28.1 cm) Richard Johnson Collection, British Library, J.17,3

The work of Muhammad Faqirullah Khan) (amal-i muhammad faqirullah khan: signature in Nastaliq script) Faqirullah, the artist who created this pictorial representation of the musical mode Bhairavi ragini from a dispersed set of ragamala paintings, was a prominent painter in Muhammad Shah’s court. His later work indicates that he moved away from the Mughal court to find patronage elsewhere. The Bhairavi ragini is the female aspect of the Bhairav raga, one of the six main modes in the Indian musical canon. The idea of the Bhairavi ragini is usually depicted by a lady worshipping a lingam, the aniconic symbol of the Hindu god Shiva. In this painting a lady approaches a lingam that is placed under the domed roof of a temple as a yogini sits in a doorway looking on. Illustrated ragamala sets were composed of either thirty-six or forty-two raga and ragini paintings that showed different aspects of the relationship between men and women, categorized by “the emotional potential of different times of the day (dawn or sunset), or seasons of the year (pre-monsoon heat or the rainy season).”

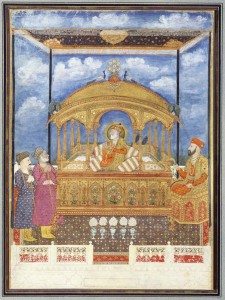

Here attributed to Khairullah (active 1800–1815) Shah Alam II (reigned 1759–1806), the blind Mughal emperor, seated on a golden throne Delhi ca. 1800 Opaque watercolor and gold on paper H. 12 13/16 x W. 9 5/16 in. (32.5 x 23.7 cm) Victoria and Albert Museum, IS.114-1986

This evocative portrayal of the blind emperor Shah Alam II (reigned 1759–1806), probably by the court painter Khairullah, highlights the continued preeminence of the Mughal emperor even as his political power was brokered through an alliance with Maratha chief Mahadji Sindhia, whose image also appears in this exhibition. In 1788, the Afghan Rohilla chief Ghulam Qadir had ransacked the palace treasury and blinded the emperor Shah Alam II in a fit of uncontrolled rage. Shah Alam’s son and successor, Muinuddin Muhammad (later Emperor Akbar I), is seated to the right on a throne platform, while on the left are two other courtiers from the emperor’s inner circle leaning on staffs. The gilded and bejeweled structures of the re-created Peacock Throne and Muinuddin’s seat, along with the five Chinese porcelain vases in the center, convey the painter’s attempt to re-create an air of luxury and opulence long associated with the image of the Mughal court.