Home / Zafar and the Uprising of 1857

Zafar and the Uprising of 1857

Bahadur Shah Zafar was the last Mughal Emperor of Delhi, and one of the most

talented and tolerant of his dynasty. Born in 1775, when the British were still

clinging to the Indian shore, he had in his lifetime seen the Mughals reduced to

political insignificance as the British transformed themselves from vulnerable

traders into an aggressive colonial government.

Zafar came late to the thone, in his mid-sixties, when it was already too late

to reverse the political decline of his dynasty. But despite this, he succeeded in

creating a remarkable court culture around him, and partly through his patronage

there took place in Delhi one of the greatest literary renaissances in Indian history.

Zafar also patronized the last great Mughal master painter, the skilled and highly

innovative Ghulam Ali Khan and his family.

Zafar was himself a mystic, poet, and calligrapher of accomplishment, but

his finest achievement was to nourish the talents of two of the greatest Urdu poets:

poet Ghalib (1797–1869), and his rival Zauq (1789–1854). While the British

progressively took over more and more of the Emperor’s power, the court busied

itself in obsessive pursuit of the most perfect Urdu couplet.

When the great Rising of 1857 broke out, Zafar found himself cast as the

figurehead of the greatest anti-colonial rebellion of the nineteenth century: the

Siege of Delhi. There were unimaginable casualties that left the city without water,

and the combatants on both sides were driven to the limits of their endurance.

After the British took the city, massacring many of its inhabitants, the last Mughal

was put on show trial in the ruins of his old palace and sentenced to be exiled. He

left his beloved Delhi on a bullock cart, and with his departure the court culture

he had nourished and exemplified collapsed. As Ghalib noted: “All these things

lasted so long as the king reigned.”

Separated from everything he loved, the last of the Great Mughals died in

exile in Rangoon, at the age of 87. The Mughals’ best epitaph was written by

Zafar himself:

Delhi was once a paradise,

Where love held sway and reigned;

But its charm lies ravished now

And only ruins remain.

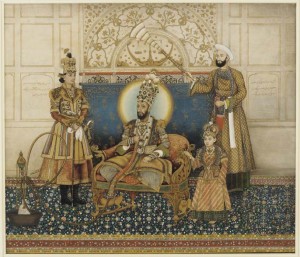

Ghulam Ali Khan (active 1817–55) Bahadur Shah II enthroned with Mirza Fakhruddin 1837–38 Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper H. 12 3⁄16 × W. 14 3⁄8 in. (31 × 36.5 cm) The Art and History Collection Courtesy of Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., LTS1995.2.105

This great Coronation Portrait of Zafar by Ghulam Ali Khan is the last great imperial portrait of the Mughal tradition. It was produced to mark Zafar’s accession to the throne in 1837. Zafar is painted against Shah Jahan’s Imperial Mughal scales of justice, and although he is weighed down with gems, his face and demeanour is nevertheless that of a Sufi ascetic. Ghulam Ali Khan has very deliberately created an image of a man who was both king and saint. Indeed, Zafar was considered a Sufi pir, and used to accept pupils, or murids. Powerless as he was, in so many ways, Zafar was widely regarded as the Khalifa, God’s Regent on Earth, and the focus of political legitimacy in northern India. As the inscription on the portrait records, he was thought

of across the subcontinent as “His Divine Highness, Caliph of the Age, Padshah as Glorious as Jamshed, He who is Surrounded by Hosts of Angels, Shadow of God, Refuge of Islam, Protector of the Mohammedan Religion, Offspring of the House of Timur, Greatest Emperor, Mightiest King of Kings, Emperor son of Emperor, Sultan son of Sultan.”

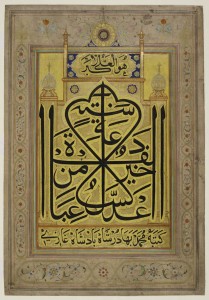

Example of Zafar’s calligraphy ca. 1850 Calligraphy on paper Approx. H. 8 × W. 6 in. (20 × 15 cm) British Library, IO Isl 3581

The talented Zafar, according to one observer, “was discussed in every house,” for “the Emperor himself was a poet and a connoisseur of poetry” and “the language of the exalted fort was the essence of refinement.” Zafar was also known for his skills as a gardener, a patron of miniatures, and a calligrapher.

Huqqa base Late 18th century Glass with gold H. 6 5⁄16 in. (16 cm) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of John Goelet, 1966, 66.844 Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Glass making, one of the most fragile decorative arts practiced in the Mughal period, enjoyed patronage into the eighteenth century. The huqqa, very much emblematic of cultural refinement and social status in this period, appears as a larger than life object in most paintings with prominently decorated bowls and bases meant for filtering and cooling tobacco, and long, snaking pipes capped with decorative mouthpieces. This bell-shaped huqqa bowl painted in gold with etched details features elegant scalloped lattice decoration.

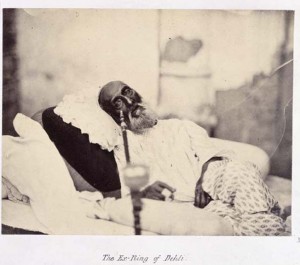

Charles Shepherd (British, active ca. 1858–78) Zafar in captivity May 1858 Albumen print Approx. H. 8 × W. 12 in. (20 × 30 cm) British Library, Photo 797/37

At the end of the great uprising of 1857, in exchange for his life, Zafar surrendered to the British Intelligence chief Col. Hodson at Humayun’s Tomb. He was taken to a small house at the back of the Red Fort near the stables and was kept there for the year between his surrender and his eventual exile. During this time he was put on display ‘like a beast in a cage’ while British troops—who had been told, inaccurately, that he was the mastermind behind the uprising—lined up to poke and insult him, pull his beard, and force him to stand up and salaam to them. This photograph of the broken and deposed Emperor is often said to have been taken in Rangoon, but according to the diary of Zafar’s jailor, Edward Ommaney, it was actually taken after the Emperor’s show trial in Delhi by the photographer, Mr. Charles Shepherd.

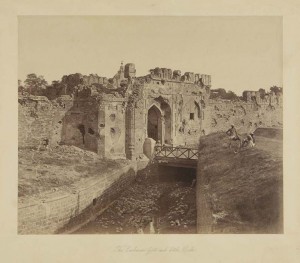

Felice Beato (British, active in India 1858–60) Kashmir Gate and ditch, Delhi ca. 1858 Salt print H. 10 1⁄16 × W. 12 3⁄16 in. (25.6 × 31 cm) Jane and Howard Ricketts Collection, London

After the recapture of Delhi, the sites associated with the siege of Delhi became popular with British tourists. The pioneering photographer Felice Beato toured Delhi and Lucknow shortly after their recapture and produced a series of images, which quickly became popular. This one shows the site of the breach in the city walls opened by the British artillery at Kashmiri Gate through which the avenging army entered the city during the assault at dawn on Monday, September 14, 1857.

Bracelet with portrait miniatures ca. 1860–70 Watercolor on ivory and gold L. 7 1⁄2 in. (19.1 cm) The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, 38.665

This gold bracelet, personifies the commercial aesthetic of nineteenthcentury Delhi, when ivory miniatures were in much demand as souvenirs. Many Delhi painters were trained in the Mughal style, and with their eye for detail and through the use of jewel-like colors, adapted to painting on ivory. Ivory miniature portraits of Indian subjects were most often facsimiles of older pictures, and were often worked into decorative ornaments such as bracelets. The three oval portraits of male subjects are: Dost Muhammad Khan, ruler of Afghanistan from 1826–1863; Bahadur Shah Zafar, the Mughal emperor who ruled from 1837–1857; and Gulab Singh, the ruler of Jammu and Kashmir 1792–1857. The female portraits were modeled on ideal types rather than actual figures.