Home / Emperors and White Mughals

Emperors and White Mughals

The sacking of Delhi by Nadir Shah was followed in 1757 by a second massacre overseen by the Afghan ruler Ahmad Shah Abdali, and 30 years later by a third cataclysm: in 1788, the marauder Ghulam Qadir looted Delhi yet again, personally blinding the Emperor and carting off his fabulous library. The resulting lack of security and patronage in the city led many artists to flee to the provinces, in particular to Lucknow and the courts of Rajasthan.

“How can I describe the desolation?” asked the poet Sauda. “There is no house from which the jackal’s cry cannot be heard. The mosques at evening are unlit and deserted. In the once beautiful gardens, the grass grows waist-high around fallen pillars and the ruined arches.”

The first British East India Company officials who settled in the melancholy ruins of Delhi were a series of sympathetic and notably eccentric figures. Politically, they saw the value of the Mughal dynasty. Personally, they were deeply attracted to its court culture. The first British Resident, the Boston-born Sir David Ochterlony (1758–1825) set the tone, adopting Indian dress, marrying Indian women, fathering Anglo-Mughal children, and building the last of the great Mughal garden tombs for himself and his chief wife.

Ochterlony was not, however, alone in his Indianized tastes. One of his assistants, William Fraser (1784–1835), underwent a similar transformation and became arguably the most discerning of all British patrons of Indian art. He supported the greatest of Delhi’s poets, Ghalib (1797–1869), and commissioned the Fraser Album, the supreme masterpiece of the period. A selection of paintings from the album are on view in this section of the exhibition.

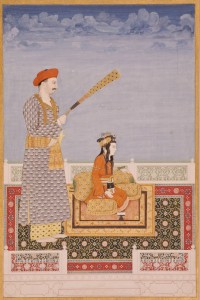

Khairullah (active 1800–1815) Mirza Salim Bahadur and Tarbiyat Khan ca. 1806–11 Opaque watercolor and gold H. 10 5⁄8 × W. 7 1⁄8 in. (27 × 18.1 cm) The San Diego Museum of Art, Edwin Binney 3rd Collection,1990.393

This exquisite rendering of the young prince Mirza Salim is one of the few known portrait studies by the veteran court artist Khairullah, who depicted three generations of the Mughal imperial family. Salim was Akbar II’s younger son, and the emperor’s favorite to succeed him on the throne after the death of his other son, Mirza Jahangir, in 1821. Salim is often shown seated or standing closest to the emperor in court portraits. Here, his status is affirmed in the lofty title “the son of the spiritual guide to the regions of the world,” further reinforced by the presence of Tarbiyat Khan, also known as Imam Baksh Khan, the emperor’s trusted aide, who is seen holding a fly whisk (morchhal) and depicted in the slightly elongated manner usually associated with the work of Ghulam Ali Khan. Salim is shown as a boy of not more than twelve years of age, his soft features and long tresses rendered with the sensitivity that was characteristic of the painter’s earlier work.

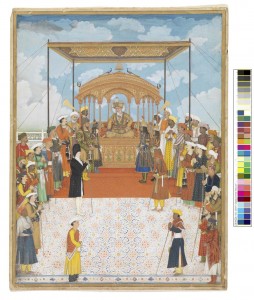

Attributed to Ghulam Murtaza Khan (active 1809–30) Akbar II in darbar with the British Resident Charles Metcalfe Delhi ca. 1811–15 Opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper Image: H. 24 5⁄16 × W. 18 9⁄16 in. (61.7 × 47.1 cm) Page: H. 25 3⁄8 × W. 19 3⁄4 in. (64.5 × 50.1 cm) Cincinnati Art Museum, The William T. and Louise Taft Semple Collection, 1962.458

“A blessed portrait of the exalted emperor of angelic hosts, prince Shadow of God, refuge of Islam, propagator of the Muhammadan religion, who makes splendid the [faith] of Ahmad [Muhammad], progeny of the House of Gurkan [Timur], choicest of the family of the Lord of the Conjunction [Timur], most magnificent sovereign emperor, sovereign son of sovereign, sultan son of sultan, lord of glories and victories, true dispenser of good things, metaphorical lord, Abul Nasr Muin ud-din Muhammad Akbar Shah Emperor, [may God extend] his kingdom and rule and give grace to . . .” (Translation of Nastaliq inscription: shabih-i mubarak-i badshah-i jamjah).

This court scene is the earliest depiction of the British Resident Charles Metcalfe in attendance at the Mughal court of Akbar II (reigned 1806–37). It is stylistically close to the work of the important court artist Ghulam Murtaza Khan, who was active in court as well as Company circles. The seated emperor is flanked by his four sons: Mirza Abu Zafar Siraj al Din Muhammad, later the emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar II), and the young Mirza Salim to his right, while Mirza Jahangir stands closest to him on his left, next to an unidentified fourth son. The emperor’s most important courtiers, including Metcalfe, are seen leaning on staffs in keeping with court protocol. Metcalfe’s starkly clad monochrome figure stands out from the other colorfully clothed courtiers.

Administrative seal of David Ochterlony 1824 Jade H. 1 5⁄8 × W. 1 5⁄8 × D. 3⁄16 in. (4.2 × 4.1 × 0.5 cm) The Art and History Trust Collection Courtesy of Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., LTS1995.2.137

Ochterlony’s Persian seal, seen here, would have been put to regular use in Delhi, since Persian was maintained as the language of all communication between the Mughal court and Company officials. He was appointed the first British Resident at Delhi in 1803, following the victory of British forces led by Lord Lake against the Maratha army. He was honored with the title Nasir-ud Daula by the Mughal emperor Shah Alam as an acknowledgment of his role in eliminating the threat of the Marathas, even though the emperor remained ambiguous about his own alliance with the East India Company. Ochterlony readily affected the local habits and manners of Mughal nobility and preferred to be addressed by his Mughal titles when in Delhi. He resided in the ruins of an old Mughal building that had once been the library of the Sufi prince Dara Shukoh, eldest son of Shah Jahan.

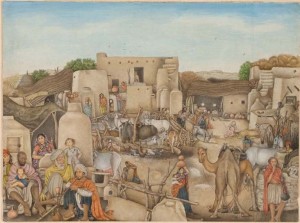

By a master artist working for William Fraser The village of Jeewah Moocuddum near Rania: William Fraser’s circle of village folk, his white stallion, and progeny From the Fraser Album Rania, Haryana ca. 1810–20 H. 12 3⁄8 × W. 16 5⁄8 in. (31.4 × 42.2 cm) Opaque watercolor on paper. Private collection

The accompanying caption mentions the subject of this painting is the village of one Jeewah (Mewah), a Rajput from Mundewal, who also appears in another group portrait in the Fraser Album on display in this exhibition. Jeewah’s son Shamoo, with his recognizable long tresses, can be spotted in the far distance leaning against a wall. In addition to being the home of Fraser’s Indian progeny, Rania was home to a clan known as Pachhada, who were subject to the new revenue settlements introduced by the East India Company in this region. Thus all of the careful depictions of fireplaces, chimneys, cattle, and young and old men in this village scene, and others from the Fraser Album may be viewed as evocative pictures of the lifestyle of the inhabitants of the Hisar region by a patron who knew the region intimately, yet understood the need for careful revenue assessment.

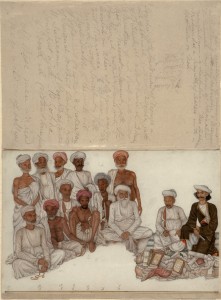

By a master artist working for William Fraser Tax collectors and village elders From the Fraser Album Delhi or Haryana ca. 1810–20 Opaque watercolor on paper H. 20 1/2 x W. 15 1/2 in. (52.1 x 39.4 cm) Private collection.

This group portrait of tax collectors and village elders accompanied by Fraser’s scribe (diwan), Mohan Lal, dressed in a white tunic and turban, and his secretary (munshi), Fuzl Uzeem, seen crouching next to Mohan Lal, is a rare view into Company operations behind the creation of the Fraser Album’s sensitively rendered portrait studies. An inscription in Fraser’s hand lists the painting as “An assemblage of Zumeendars in Cutcherry with my Moonshee and Deewan. The Munshee Fuzl Uzeem of Khairabad near Lucknow — a moosulman. The Deewan Mohan Lal a Kayuth of Dehlee with spectacles on nose.” This is followed by a list of all the attendees, who “are mostly headmen and elders of villages.”

A re-creation of the Mughal emperor Akbar II receiving a European officer ca. 1840 Opaque watercolor and gold H. 17 11⁄16 × W. 15 5⁄8 in. (45 × 39.7 cm) The San Diego Museum of Art, Edwin Binney 3rd Collection, 1990.394

In this painting, Akbar Shah, seated on a palanquin, is approached by a European officer in the grounds of the Delhi palace. Behind him, his son Mirza Jahangir rides on horseback. The imperial procession is made up of Akbar Shah’s coterie of ministers, attendants, and footmen carrying spears. The mood is animated, as some of the men seem to be engaged in conversation about the officer who, dressed in a black top hat and coat, is looking up at the emperor with folded hands. While it is possible that the bespectacled European is Archibald Seton, the second Resident at the Mughal court, the style of his civil attire and the treatment of the landscape suggest that this painting was executed in the period after the death of Mirza Jahangir in 1821. The subject of this painting may be Seton communicating the Company’s refusal to recognize the dashing Mirza Jahangir as imperial heir (depicted at the right side of the painting and raised to the same level as his father, the Emperor).

Sir David Ochterlony (1758–1825)

The Boston-born Sir David Ochterlony was twice British Resident (or ambassador) at the Mughal court in Delhi, and liaised with the Emperors Shah Alam and Akbar II. He was born in Boston, where his family fought with the losing British loyalists, and moved to India in 1777 after the Patriot victory at Yorktown.

With his fondness for huqqas, nautch girls, and Indian costumes, Ochterlony cut a lively figure, amazing Bishop Reginald Heber, the Anglican primate of Calcutta, by receiving him sitting on a divan wearing a Hindustani jama and a turban, all the while being fanned by servants holding a peacock-feather fan (pankha). To one side of Ochterlony’s own tent, wrote Heber, was the red silk harem (shamiana) where his women slept. Ochterlony’s cortege, which the bishop later spotted on the move through the country of Rajputana, was equally remarkable: “There was a considerable number of horses, elephants, palanquins and covered carriages,” wrote Heber. According to Delhi gossip, Ochterlony had no fewer than thirteen Indian wives; every evening during his years in Delhi he was said to have taken all thirteen on a promenade between the walls of the Red Fort and the river bank, each wife on her own elephant.

Yet Ochterlony, like many figures of his age, lived a double life. By night,he lived in Mughal style with his Mughal wives, as seen in his celebrated image on view here, dressed in turban and kurta pajamas watching his dancing girls. Yet by day he upheld the prestige of the Company, fighting with distinction in the Anglo-Maratha war of 1803–5, and the Nepal War of 1815, as well as playing a prominent role in the Company’s political service.

William Fraser (1784-1835)

When the wife of the new British commander in chief in India visited Delhi in 1810, she was horrified by what she saw there. It was not just the British Resident at the Mughal court, Sir David Ochterlony, who had “gone native,” she reported; his two assistants were even worse: “They both wear immense whiskers, and neither will eat beef or pork, being as much Hindoos as Christians.”

One of these men, William Fraser, a Persian scholar from Inverness who went on himself to become Resident at the Mughal court and lived in Delhi for three decades, made perhaps the most interesting journey of any British figure of the period, transforming himself from a self-exiled Scottish landowner to a White Mughal with an Indian family, a private army, and close relationships with some the most interesting artistic, theological, and political figures of the period.

Fraser became a crucial figure in Delhi’s artistic development: the Fraser Album, which he commissioned, was the landmark masterpiece of the period and its portraits of soldiers, noblemen, holy men, dancing girls, and villagers, as well as his staff and his bodyguards, are unparalleled in Indian art. Particularly remarkable are the images the Fraser Album contains of the village of Rania, some of which are on view here. Rania was home to Fraser’s mistress, Amiban, and his two Anglo-Indian sons, and daughter. Fraser’s connection to the village means that there is an intimacy here quite unlike the usual colonial commissions. The wild-looking and handsome villagers, superbly painted with a realist flourish by a master portraitist, were intimately known by Fraser, and formed part of his circle of acquaintances — as he wrote himself, the images recorded “recollections that never can leave my heart.”

Sir Charles Metcalfe (1785–1846) and Sir Thomas Metcalfe (1795–1853)

Charles Metcalfe and his younger brother Sir Thomas Metcalfe (1795– 1853) dominated the Delhi Residency for the final few years of the Mughal court. Between them they oversaw the slow increase in the power of the East India Company in Delhi and the steady diminution of that of the Emperor. Initially an assistant to David Ochterlony in 1806, Charles Metcalfe rose to be Resident in 1811. Metcalfe fit in with the tone of the time, building a house in the Shalimar Gardens and fathering three sons by the Sikh bibi he had met at the court of Ranjit Singh. But by the time of his return to Delhi as Resident in 1826, Metcalfe had abandoned his bibi and had begun to assume a very different attitude to India and its Mughal rulers. “I have renounced my former allegiance to the house of Timur,” he announced in 1832.

Thomas Metcalfe completed the work begun by his older brother Charles. Much of the his professional life was dedicated to laying the groundwork for abolishing the Mughal dynasty, and for negotiating a succession settlement that would allow the Company to expel the Royal Family from the Red Fort on the death of Zafar. Yet Thomas Metcalfe’s attitude to Delhi and its ancient Mughal traditions was much more ambiguous than this might suggest. He founded the Delhi Archaeological Society, and between 1842 and 1844 and commissioned a series of images of the monuments, ruins, palaces, and shrines of the city from Mazar Ali Khan. He later had the images bound into an album, titled The Dehlie Book, and wrote a descriptive text as an accompaniment. This, along with the fabulous panorama of the city of Delhi on view in this exhibition, which he probably commissioned around the same time, provide the two most detailed surviving pictorial records of the city in its last renaissance before the cataclysm of 1857.