Coal+Ice at 17,723 ft.

GlacierWorks founder and COAL+ICE photographer, David Breashears was inspired to get people thinking about the relationship between coal use, climate change and the fate of the Himalayan glaciers. He decided to take a selection of the coal mining photos with him on a trek to Mount Everest Base Camp, where he displayed the photos in a natural “ice gallery” on the Main Rongbuk Glacier. Reached by phone at his home in Marblehead, MA, Breashears discussed with Leah Thompson, COAL+ICE Associate Producer, what it was like to stage a photography exhibition at 17,723 feet above sea level.

David, you’re no stranger to creating photography exhibits at and around Mount Everest Base Camp. You’ve done a few exhibits of your match prints up there, but how have climbers reacted to COAL+ICE?

They had a lot of questions. First question was, what are you trying to accomplish here? And once I explained that these images are part of the COAL+ICE exhibit at Three Shadows in Beijing and how we wanted to bring the images into the context of the conversation, then they understood it. It was something they hadn’t seen before and would never expect to see at Base Camp, at 17,600 feet. People are there to climb. They sit in their tents and eat and read. After looking at the photos the response was first one of fascination and then one of contemplation. They hadn’t seen that connection made before. And for me that connection was, what impact will burning cheap coal, and more of it over the next 50 years, have on the high alpine environment and the glaciers of the Greater Himalayan region. Are the consequences sustainable or are there going to be some very negative outcomes if we continue along this path?

How difficult are the logistics for an “ice gallery”? What is involved?

We have created the “ice gallery” twice. The first attempt, which you see in this video, was on the north side. The logistics on the north side, on the Main Rongbuk Glacier, are much more difficult because we don’t have the same system of support, lodges, pack animals and porters, which supply the trek route to Everest Base Camp. So on the north side it was myself, two Sherpas, the cinematographer and four Tibetans carrying around our entire camp, stoves and sleeping bags and tents and food, and all the video and camera gear, and also the materials to build these frames. We had pre-cut our frames in Katmandu before crossing into Tibet, but we had to glue and assemble them together at Rongbuk Monastery at 16,200 feet and it was quite cold there in December. We had to make a camp on the merrain above the ice gallery, and it was quite windy and cold and our challenge was, since it was a bit of an experiment, to find a way to attach the photos to the ice. The light was moving very quickly, the shadows were quickly converging upon the gallery space, and the wind kept blowing the pictures over.

When we did this a second time on the south side, we had the advantage of the support of a very large basecamp and the prints came up the “highway to Everest.” It is still a seven-day hike from Lukla, where the prints arrived by plane. It took us a day to build the frames and two days set up the images in the ice cavern and by then it was May 10th and the sun was so intense the images would melt out of the ice. That is why we decided to take the photo of the gallery at night and light it, because at night the photographs would stay frozen in place.

What motivates you to undertake a project like this?

It is quite exciting for us to evoke another way to look at these images. Not only is there a graphical beauty to the contrast of the ice in this high cold place with these images of coal, which provide heat and energy to the world, but that contrast starts the conversation — what does this mean, this growing dependency on coal around the world? It causes people to think in a different way about our relationship to our energy sources and to these glaciers.

How long have you been going to Mount Everest? When did you first notice changes?

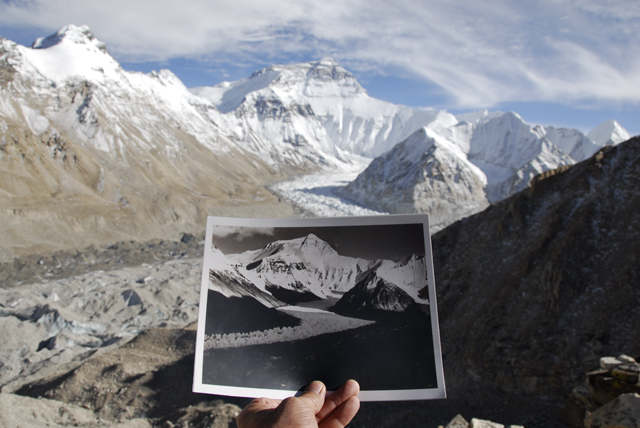

I first went to Everest in August of 1981 to the Kangshung Face in Tibet. I had read about the changes, but you don’t notice it if you go there yearly. You are a part of it. But until October of 2007, I went there with Frontline to find a match photo for the iconic George Mallory photo in 1921, I didn’t know the scale of the change. I was just astonished when I held that photo out [below], I didn’t need to take a match photo to see the change. I could see where that glacier had been sitting in 1921 by looking at the rock walls in front of me.

Whenever you camp at Base Camp on the south side, and you erect your tent in late March and take it down in late May, you have essentially created a form of insulation or shade for a certain space on the glacier. Sometimes you have to climb up to five feet back into the tent as the surrounding ice melts away. I knew if that was happening over two months, then what was happening over the entire warm season? But then you have to ask yourself, of the much [more] vertical loss, how much is being replaced during the snowy season. That was a subtle way of knowing something was changing before I took the Mallory picture back to Everest in 2007, but I was bereft of information on the scale of it. But each of the comparative photos we have taken has confirmed a significant loss.

The terrain is quite different than it was 80-100 years ago. I read accounts of the early expeditions crossing glaciers with hardly a mention of how difficult it was, easy hikes that would take half a day. Some of these glaciers can no longer be crossed. We will approach a place in order to conduct some match photography and we ask ourselves, how can we possibly get over there, to the other side of the glacier where the original photo was taken? We have the benefit of a higher skill level and better equipment, but the difference between the ease with which they crossed the glacier and the fact that we find it almost impossible to cross, the gap in that equation is soon provided by the match photo. These are basically two different glaciers. The early photo shows a glacier 300 feet higher and mostly flat and this one is quite treacherous, filled with crevasses and ice pinnacles.

The New York Times wrote a story recently about the connection between climate change and increased risk in mountain climbing — is this something you’re encountering?

Increasing amount of evidence is pointing to climate change affecting regional weather and we might be seeing some of that happening in the Alps and elsewhere when we see these heavy snows at a time when climbers don’t expect them. But I am careful about equating climate change and weather, but of course if summer snowstorms in the Alps become a multi-year trend, then that will be significant. This trend is certainly one scientists will be paying a lot of attention to.

What will we see from GlacierWorks next?

There will be more expeditions. We are trying to get photographic documentation of glaciers along the entire Himalayan range. It is a long range, an arc of 14,000 miles, and the glaciers are responding differently to climate change, so we want to have a full overview. We are also working with Microsoft Research’s Rich Interactive Narratives (RIN) project, which will make our web presence more interactive and compelling and will develop our website into a STEM teaching tool based on climate change and earth sciences.

Photos displayed in the two ice galleries by Geng Yunsheng, Yang Junpo and Niu Guozheng.

This post is also available in: Chinese (Simplified)