Home / Interview with the Artist

Interview with the Artist

Telephone interview with Yoshihiro Suda

Conducted by Miwako Tezuka, Associate Curator, Asia Society Museum

April 14, 2009

Miwako Tezuka: What motivates or inspires you to create art?

Yoshihiro Suda: Basically, I like to carve wood, and I like plants and flowers. I also like installation art, so putting all these together becomes my work.

MT: Where does your attachment to plants and flowers come from?

YS: I grew up in the countryside in Yamanashi prefecture, Japan, and I moved to Tokyo when I was eighteen to attend Tama Art University. When I was living in the countryside, I had no interest in nature, but after I moved to the city, I suddenly developed an interest in it. I would go to flower shops to buy flowers, and I started to pay attention to small weeds on the sides of the streets. At around the same time―I was probably about twenty years old or so―I also became interested in traditional Japanese art and art history.

MT: Perhaps that is not a coincidence because traditional Japanese paintings are filled with motifs from nature, such as blossoming flowers and plants of the four seasons.

YS: Yes, that is true. At the time, I was also interested in Buddhist sculptures and paintings.

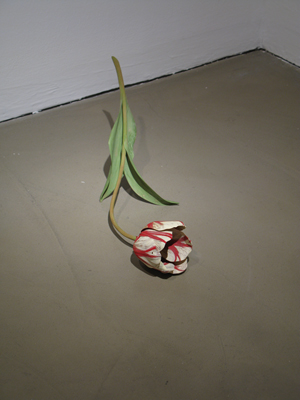

MT: Although there have been some exceptions to this—such as your camellia installation in Naoshima Island—you generally choose a single motif, such as a single rose or a small group of weeds, and install that small work in an unexpected place.

YS: I also once installed 108 weeds in an exhibition at the Marugame Genichiro-Inokuma Museum of Contemporary Art in Japan.

MT: 108, like the number of worldly attachments in Buddhism. Have you tried any other forms of installation, and if not, why?

YS: I can’t make anything big! In terms of the scale of art, I think there are artists who are naturally able to make large scale works—a number of American artists, in fact. I am simply different from them. When I was in school, I did many drawings and carvings of things other than plants and flowers, but I always felt most comfortable with plants and flowers. I keep making my nature-motif sculptures because I am not yet tired of them. Recently, I have been feeling that the pace of life is too fast. New devices and technologies are introduced one after another, but we humans cannot necessarily evolve at the same fast pace. For anything that demands technique, like art, you have to spend the time to gradually develop your skill.

MT: This sounds like the theory of a craftsman.

YS: I think they are much better disciplined than I am!

MT: How does your work develop? Do you choose the motif of your sculpture before you see an exhibition space, or does the space inspire you to create a certain work?

YS: Right now, the space is more important to me. I carve small things, but even those small and often overlooked things have the potential to change our way of seeing a space. I think art can change our perspective and ways of thinking. It encourages us to see things that we otherwise might miss.

MT: Your sculptures are made from magnolia wood, and you often carve magnolia flowers. Is there any special meaning behind the magnolia?

YS: I like its shape, and I have done some research about its genealogy. The first flowering plants emerged on Earth about 140 to 150 million years ago, and the magnolia was one of the first plants to have blossoms. It evolved into its current shape about one hundred million years ago, and essentially, it has not changed since. I like the sense of history that emanates from this flower. There are different types of magnolia in the world, but in Japan, the most common is called hoonoki, and this is what I use as my material. To me it feels soft and easy to carve. I also like the fact that the magnolia flower is recognized everywhere, and you can find it in many different countries, both growing naturally and planted in parks. I often have this fond feeling toward things that exist in the everyday environment.

MT: For the Asia Society exhibition, you are creating a new magnolia flower sculpture and exhibiting it along with works from the Society’s collection that you have selected. Can you talk about this?

YS: I think this is the first time I have worked on a project like this, creating a new work intended to be shown alongside traditional artworks. In Japan, I once installed a tiny weed sculpture near the foot of a Buddhist statue that is designated as a national treasure. This was at the Okura Shukokan Museum in 2000. But that happened almost by coincidence because my work just happened to fit in the small gap between the pedestal and its plexiglass bonnet. It was a happy coincidence, really. A well-known figure in Japanese art history saw this installation and mistakenly criticized the museum for what he thought was neglectful maintenance; after being told that it was a contemporary art installation, however, he approved of the concept.

What I am doing for the Asia Society exhibition is very different. In 2008, I was in New York to survey Asia Society’s gallery space. On the way there, strolling through Central Park, I noticed white magnolia flowers in bloom and thought, “Oh, here you are again.” When I got to Asia Society, I found that there was an exhibition of Korean ceramics [First Under Heaven: Korean Ceramics from the Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection] in the gallery where my show would be installed. I thought the collection works were splendid, and they left an impression in my mind of being very white, so I decided to create an installation that focuses on the color white. My experiences in Central Park and at Asia Society with the Rockefeller Collection came together naturally. In this sense, this project differs from my usual approach of setting the space as the starting point for the development of an installation idea.

MT: You spoke about your previous installation that used “a small gap.” How do you decide where to position your work, and what would you like people to see?

YS: I personally like small corners or marginal spaces—suki-ma, literally “empty space” in Japanese. I feel comfortable in them. What makes up a space is not just its center but its peripheries: everything including its corners. If my work can make people notice something that they would normally dismiss, I think that is good.

MT: There is a possibility that some might not even find your work.

YS: “Cannot be seen” is also part of the spectrum of “seeing.”