Reference

Edo

Edo (modern Tokyo) grew from a swampy outpost into a metropolis after the Tokugawa shogunate established it as their seat of government in 1603. By the early eighteenth century, it was the largest city in the world with over a million inhabitants. Edo flourished and became a magnet for literati, artists, craftsmen, entertainers, merchants, and others ministering to the needs of samurai and leisured townsfolk.

The two great hubs of Edo social life were the kabuki theater district downtown and the pleasure quarters, which were relocated to the northeastern outskirts of the city after a devastating fire in 1657. A square fence enclosed this pleasure quarter, and the only entrance was through the Great Gate on the center of the north side. A wide central street, Nakanochō, divided the quarter into equal halves. Because of its distance from the city center, tea houses and restaurants opened along the Sumida River to cater to people on their way to the quarter, making trips to the Yoshiwara enjoyable outings.

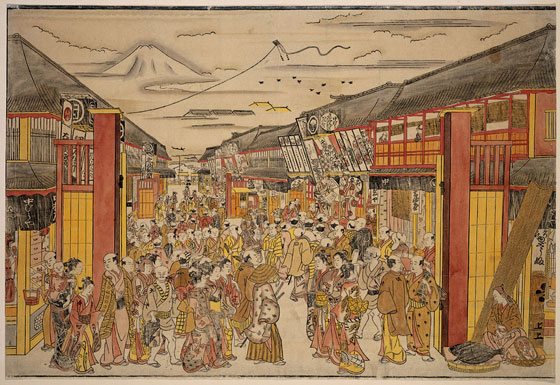

Figure 1.

Okumura Masanobu (1686–1764).

Large Perspective Picture of the Kabuki Theater District in Sakaichō and Fukiyachō.

ca. 1745.

Woodcut, handcolored.

43.8 x 64.5 cm.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, William Sturgis Bigelow Collection, 11.19687.

Photo: © 2008 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Figure 1.

Okumura Masanobu (1686–1764).

Large Perspective Picture of the Kabuki Theater District in Sakaichō and Fukiyachō.

ca. 1745.

Woodcut, handcolored.

43.8 x 64.5 cm.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, William Sturgis Bigelow Collection, 11.19687.

Photo: © 2008 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Edo’s bustling theater district was located downtown in the central business districts near Nihonbashi, where many publishers of prints and books had their shops. With the rapid rise of the two great focal points of popular desire—the “entertainment quarters” and the theaters—subjects were soon found in courtesans and actors identified, idolized, and imitated by a fashion-conscious public.

The Technique of Japanese Printmaking

The process of print-making was a collaboration between publishers, artists, block cutters, and printers. Tijs Volker (1892�1979), a curator at the National Museum of Ethnology, Leiden, The Netherlands, coined the term "ukiyo-e quartet" to describe the cooperative enterprise of these professionals, with the publisher acting as the financial and aesthetic arbiter of the process. A publisher would approach an artist to create a design for which the publisher saw commercial potential. (In other cases, an individual or poetry club might engage an artist for a limited private commission, called a surimono.) The artist would do a rough sketch and then discuss color choice and other specifics with the publisher, who would see the design through production.

The final drawing for a woodblock print was traced onto very thin paper and given to the block cutter who would paste the tracing face down onto the block and carve the design in high relief. Lines were cut following the direction of the brush strokes of the original drawing. The first block, called the key block, provided the black outlines for the print and acted as a guide for the color blocks. Separate blocks were cut for each of the colors, so blocks were often carved on both sides to cut costs. After the blocks were carved, and the colors approved, the printer then created the prints. The printer placed the pliant paper onto an inked key-block and impressed the ink onto the paper by rubbing the paper with a round rubbing pad made of paper and bamboo fibers called a baren (see the item in the woman's right hand in fig. 2). The process was repeated for each color until the entire, fully colored print was completed.

For an in-depth interactive review of the Japanese printmaking process, see: http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/pharos/sections/making_art/index_japan.html

This imaginary scene shows a woodblock carver and his female assistant carrying out the printmaking process. While the implements and techniques shown are accurately portrayed, women did not work as block carvers or printers during the Edo period.