1873 Liang Qichao’s Birth

Liang Qichao is born on February 23, 1873 in a village of farmers and fishermen in Xinhui, a southern Chinese county in Guangdong province. Liang came from a relatively wealthy family of local gentry. Given a traditional Confucian schooling, Liang quickly emerged as a prodigy, passing the local examinations at 11 and the provincial examinations at 16. Like Wei Yuan and Feng Guifen before him, however, Liang found the national exams in Beijing a sterner test.

Xinhui County, Guangdong, China

Indeed, the Chinese obsession with starting anew can be said to begin with Liang. He was the first in a century-long line of intellectuals and politicians who, like magicians locked in a glass coffin filling with water, took on the challenge of freeing themselves and China from remaining drowned in 'old thinking.'

page 92

1890 More on Kang Youwei

Kang Youwei (1858–1927), along with Liang, was one of the most important reformist thinkers of the late Qing period.

Kang Youwei

Kang met Liang Qichao in Beijing in 1890, after his first failed attempt to pass the highest level of the imperial examinations. Kang introduced the younger Liang to a bold teleological reinterpretation of Confucian thought, inspired by some of the same scholarship that influenced Wei Yuan. Liang went on to become one of Kang’s star pupils at his radical school, the Cottage in the Woods Academy.

1896 The “Sick Man of Asia”

China’s 1895 defeat to Japan and the resulting Treaty of Shimonoseki (read more about the treaty in the chapter on Empress Dowager Cixi) opened the eyes of many Chinese intellectuals, Liang included, to China’s weakness. The treaty inspired Liang to coin the now famous phrase, “Sick Man of Asia,” to describe China’s precarious position. The phrase in Chinese is dongfang bingfu (东方病夫), first appearing in an article by Liang in a Shanghai newspaper in 1896.

1896 Liang’s First Forays into Journalism

In 1896, disheartened by his failures in the imperial exams, Liang joined the editorial board of a new Shanghai paper called Chinese Progress. Though he only remained at Chinese Progress a short time, Liang become convinced “that a dynamic popular press was a key to national strength.”

"In his skillful editorial hands, a series of journals and newspapers would exert the kind of powerful influence on early twentieth-century Chinese public opinion that online journalism has exerted in recent decades."

Page 96

1897 Early Influences on Liang’s Thought

Liang moved to Hunan province and began teach pupils of his own in 1897. There Liang began to think more deeply about the adoption of Western reform in China. He edited an anthology of Wei Yuan’s work, read Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis, and began teaching a revolutionary curriculum combining Western thought with Chinese classics. Studying the West, Liang came to think that the West’s recent superiority over China lay in its scientific and philosophical foundations.

Sir Francis Bacon

1897 More on Yan Fu

Yan Fu (8 January 1854 — 27 October 1921) was one of the first Chinese scholars to study abroad, attending Greenwich Naval College in 1879. He brought back to China a conviction that “his country’s only salvation lay in learning how to compete in the new global scramble for power.” His outspoken reformist ideas became especially influential in the wake of China’s defeat to Japan in 1895. In this period, he and Liang were both searching for pragmatic solutions to China’s problems. Yan believed he had found a solution in the doctrines of Social Darwinism. Yan’s translations of Herbert Spencer, who coined the term “survival of the fittest,” and John Stuart Mill were important influences on Liang’s intellectual development.

Yan Fu

1898 A Brush with the Emperor and Exile in Tokyo

Liang briefly rose to the very highest levels of prominence during the Guangxu Emperor’s Hundred Days Reforms. But when Empress Dowager Cixi quashed those reforms, Liang fled to Japan with his mentor Kang Youwei.

The Japanese government welcomed Liang in Tokyo and gave him the wherewithal to give voice to the growing community of Chinese dissidents living overseas. Liang briefly flirted with allying himself with Sun Yat-sen’s revolutionary republican group, but eventually set out on his own.

Yokohama Chinatown in 1903

1902 Liang’s Writings from Japan

Liang spent 14 years in Japan all told, finding his calling as a journalist among the Chinese expats in Yokohama. He first attempted to promote his views on Chinese reform through a journal he created, Remonstrance. When a fire destroyed Remonstrance’s printing house in 1901, he founded his most famous journal, New Citizen.

Liang was widely read on the mainland, reaching as many as 200,000 readers, and his opinions on politics and reform were extremely influential.

Liang was one of the first Chinese intellectuals to embrace the idea that China’s traditional value system might have to be torn down to make way for a new system. In this regard, he may have been influenced by Japanese Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi. Liang coined the term “destructivism,” or pohuai zhuyi (破坏主意), that would letter echo through the writing of more violent figures like Mao Zedong.

Many issues of New Citizen are digitized and available online (in Chinese).

An issue of Liang’s journal, New Citizen

1903 Liang Visits the U.S.

In 1903, Liang traveled the world, visiting Singapore, the Philippines, Australia, Canada and most importantly, the United States. Liang criss-crossed the country, spoke to President Roosevelt and J.P. Morgan, and visited San Francisco and New York’s Chinatowns.

Liang’s trip led him to several important epiphanies about China’s struggles, concluding that Chinese people were not suited for the freedom of a Western political system.

We

can

only

accept

despotism

and

cannot

enjoy

freedom…

When

I

look

at

the

societies

of

the

world,

none

is

so

disorderly

as

the

Chinese

community

in

San

Francisco.

Why?

The

answer

is

freedom.

The

character

of

the

Chinese

in

China

is

not

superior

to

those

of

San

Francisco,

but

at

home

they

are

governed

by

officials

and

restrained

by

fathers

and

elder

brothers…Now,

freedom,

constitutionalism,

and

republicanism

mean

government

by

the

majority,

but

the overwhelming

majority

of

the

Chinese

people

are

like

[those

of

San

Francisco].

If

we

were

to

adopt

a

democratic

system

of

government

now,

it

would

be

nothing

less

than committing

national

suicide.

…

To

put

it

in

a

word,

the

Chinese

people

of

today

can

only

be

governed

autocratically.

…

More translated excerpts from Liang’s “Observations” on his American trip are available from Columbia University’s Asia for Educators project.

Liang’s political leanings lacked consistency, drifting from his brief flirtations with Sun Yat-sen’s Republicans, to musings on Democracy, to calls for “enlightened despotism.” His opportunity to put his theories to the test was finally approaching, however. With Cixi’s death in 1908 and the Qing Dynasty crumbling, Liang Qichao became eager to take the reins in China himself.

San Francisco Chinatown, 1898

Like Feng Guifen writing about Lincoln's America back in the 1860s, the pioneer of Chinese liberalism now suddenly found himself starkly questioning democracy's appropriateness for his country, even as he embraced the United States in theory as the world's ideal political system.

Page 106

1913-1915 Liang’s Failure under Yuan Shikai

With the sudden and anti-climactic collapse of the Qing in 1911, Liang saw his chance to throw his hat in the ring politically. Estranged from Sun Yat-sen’s party, however, Liang decided to support the opposition, led by Yuan Shikai.

Yuan Shikai (1859–1916) was an important Chinese general, an ally of Li Hongzhang during China’s late Qing military modernization. When the winner of China’s first and only free elections, Song Jiaoren, was assassinated in 1913, Yuan came to power under a cloud of suspicion. Yuan proved autocratic and self-serving, quickly outlawing all opposition and eventually attempting to enthrone himself as a new emperor.

Yuan Shikai

Liang’s political career under Yuan was brief and ineffective. Turned off by Yuan’s despotic turn, Liang quickly resigned. He found more comfortable footing as an instigator of popular outrage at Japan’s infamous Twenty-One Demands.

1919 Liang’s Disappointing Trip to Europe

In 1917, China joined the fight against the Germans in World War I, partly in hope of securing a stronger position in global affairs should the French and British allies prevail. Japan had committed to the war three years earlier, on the same side.

Liang traveled to Europe as China’s envoy to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and was stunned to find that Japan had outmaneuvered China once again. Tokyo had made deals with the allied powers to assume control of Germany’s China concessions. Most disturbing to Liang and the Chinese people, these “secret” deals were known to China’s president, who, in debt to Japan, had not objected. Dismayed, Liang spread news of the betrayal back home, sparking the outbreak of the May Fourth Incident.

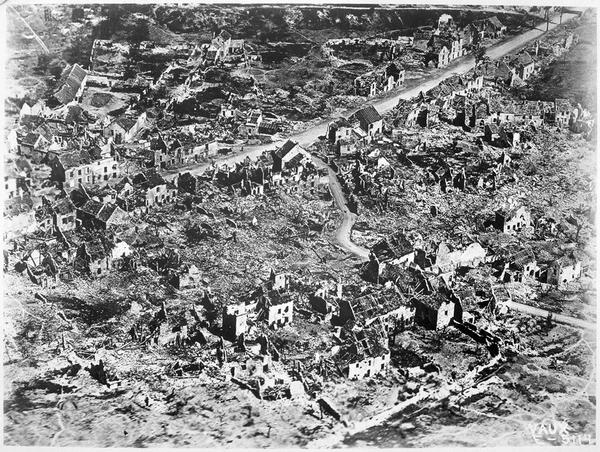

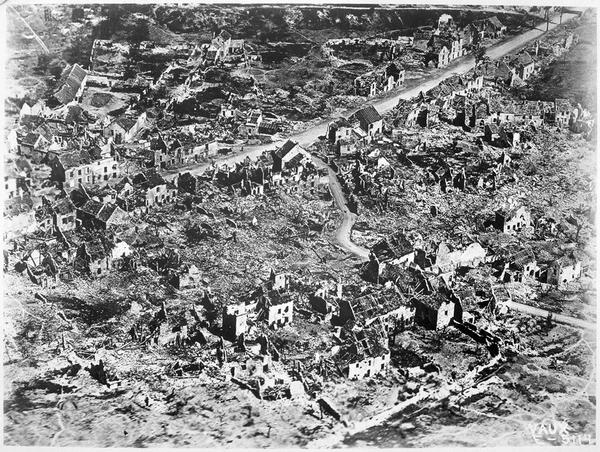

Liang set off on a tour of Europe and was shocked by the devastation he found. Liang found himself “horrified by the postapocalyptic scenes,” and began questioning whether the Western scientific and philosophical models so idolized in China might have played a role in the tragic outcome.

Aerial view of the ruins of Vaux in France

The man who had done so much to open his countrymen's eyes to Western thought and civilization found himself staring into the self-destructive heart of what Oswald Spengler was calling, in his zeitgeist-catching new book, Decline of the West, its "Faustian" bargain with the devil.

page 111

1929 Liang’s Drift Back to Tradition and Death

Returning to China in 1920, Liang retired from political life. He returned to journalism, editing a new publication Emancipation and Reconstruction, focused on importing new economic ideas from the West. He died of cancer in 1929, in Beijing.

Like Wei Yuan and Feng Guifen, Liang drifted back towards his traditional Confucian and Buddhist roots as he aged.

While he stands out as a great thinker, perhaps his most important legacy was a lasting influence on a young Hunanese librarian with an insatiable appetite for Liang’s dispatches from Japan, Mao Zedong. Mao took Liang’s theories about destruction to heart, with earth-shaking ramifications for China’s development.

Liang Qichao’s tomb in Beijing

"The nihilistic genie that Liang had begun to conjure up would later be let out of the bottle by Mao to wreak a havoc that Liang could not have imagined."

104-105