|

|

|

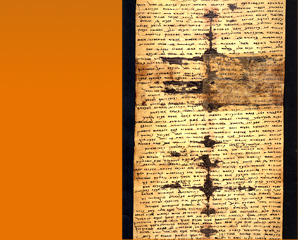

Men of Sogdiana have gone wherever profit is to be found. — New Tang History, ca. 9th century The most successful traders of the Silk Road were the Sogdians, an Iranian people who inhabited the region of Transoxiana (corresponding to the modern-day republics of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) in Central Asia. Indeed their language became the lingua franca of the Silk Road. Already by the fourth century, the Sogdians had established numerous communities in China, particularly in Gansu and Ningxia. The Sogdians were not only merchants; they were also interpreters, entertainers, horse breeders, craftsmen, and transmitters of ideas. Sogdian scribes were among the first translators of Buddhist texts into Chinese. The majority of Sogdians, however, retained the Zoroastrian beliefs and practices of their homeland and built temples in their communities in China. The Chinese were fascinated by the Sogdians' religious rituals and the uninhibited dancing that took place in these temples. Cemeteries at Guyuan and Yanchi in Ningxia are two of the few sites directly relating to Sogdians discovered so far, and the most important archaeological evidence of these communities. The occupants were members of the Shi clan whose ancestors had migrated from Kesh, a Sogdian city south of Samarkand. The Guyuan tombs reveal a complex mix of indigenous Chinese and exotic traditions. The tombs themselves were conventionally Chinese in structure, and many of the contents were Chinese. But other objects were either imported or inspired by foreign types or technology. The tombs thus testify both to their owners' adoption of Chinese material culture and to and the links they retained with their ancestral homeland far to the west. Trade along the Silk Road was conducted using a combination of barter and monetary exchange. Silk, exported in huge quantities from China, was in effect a form of currency (it was also a form of tribute used to buy off the nomads), but due to its perishable nature relatively little has survived. Coins, on the other hand, have been found at widely dispersed sites along the Silk Road, providing evidence of routes, the circulation of currencies, and of cultural exchange. The two major currencies of the Silk Road, the silver drachm of Sasanian Iran and the gold solidus of the East Roman or Byzantine empire, were struck (stamped) from precious metals. Because their metal was never debased nor their weight reduced, they were ideal for transnational trade. Chinese coins were cast bronze and enjoyed little circulation outside China. Numerous Sasanian and Byzantine coins have been found in Gansu and Ningxia, particularly in the tombs of officials and merchants of foreign descent. However, it is not certain to what extent they were used as currency, since some are pierced for use as pendants or clothing embellishment and others are not true coins but imitations. |

||||