Home / Interview with the Artist

Interview with the Artist

Email interview conducted by exhibition curator Miwako Tezuka, December 2010–February 2011.

Miwako Tezuka:

Can you briefly describe your early background in science, and when and how you discovered your passion for art?

U-Ram Choe:

My parents majored in painting when they were in college, and as their son I was naturally inclined towards art. Growing up watching a lot of TV shows that featured robots, I enjoyed making and drawing robots and as a child I wanted to become a robot scientist. During my high school years, I began to dream of becoming a sculptor and this is what I pursued. In my junior year of college, though, I came to learn about kinetic art and my childhood dream began to resurface. For the first time I used motors in my artwork, and I was so excited about the idea that machines could come alive. Since then I have been working on the idea of animating machines with life. I guess the source of my creativity is completely genetic—a combination of my parents’ artistic talent and the skills of my grandfather, who was a mechanic.

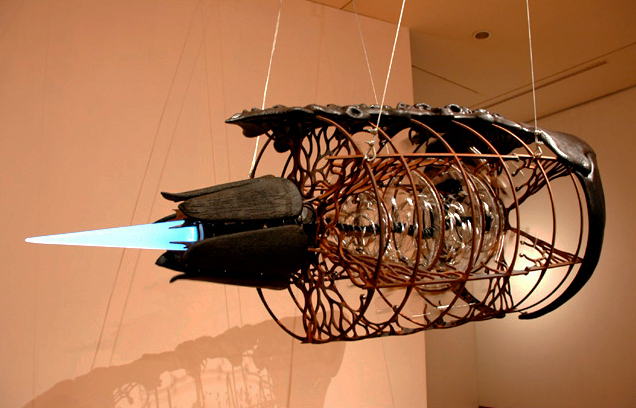

Jet Hiatus, Scientific name: Anmorosta Cetorhinus maximus Uram, 2004

Steel, acrylic, machinery, synthetic resins, acrylic paint, custom CPU board, LED, motor

H. 88 x W. 222 x D. 85 cm

Lumina Virgo, Scientific name: Anlusensta Luciola lateralis Uram, 2002

Metallic material, Touch Sensor, light bulb, magnet

H. 8 x W. 31 x D. 26 cm

MT:

In your previous works, your main interest seems to have been the evolution of inorganic materials into organic, living things that you call “anima-machines.” To me, they were about an alchemical transformation with a quasi-scientific sensibility. In recent years, while this scientific curiosity is still there, you seem to have begun further explorations into greater, cosmic changes and movements, and the invisible forces behind them—which we might call some sort of spiritual presence. Do you see a difference in the direction you are taking now compared to your past work? If so, what opened this new perspective for you?

UC:

I have a habit of watching viewers react to my work. The moment my piece starts moving, some viewers seem to marvel as if they were seeing a religious icon in a temple or cathedral. Others react almost as if facing the grandeur of nature, like seeing the Grand Canyon for the first time. Observing their reactions, I have wondered what art, religious icons, and natural wonders may have in common. I believe the common element may be the sense of wonder we feel when we encounter something that goes beyond the realm of logic and seems to transcend the death and suffering that we are bound to as human beings.

It seems that my work evokes similar wonder for viewers since it goes beyond reason. This experience has inspired me to pursue works that use mechanical movement to induce transcendental experiences. My first experiment was to try finding a perfect form. While traveling the United States, I got to thinking that a god’s image—a perfect form transcending biomorphic forms—might already reside somewhere in the universe. I started to make my own new mythic story about such a god. It was inspired by ecological stories I had written for my anima-machine series. Throughout history, myths have included many metaphors about human life and its essence. I thought if I used the form of myth I could make a link between the real world and the spiritual world. The new anima-machine, Custos Cavum, for Asia Society’s In Focus exhibition, draws images from this new myth I just wrote.

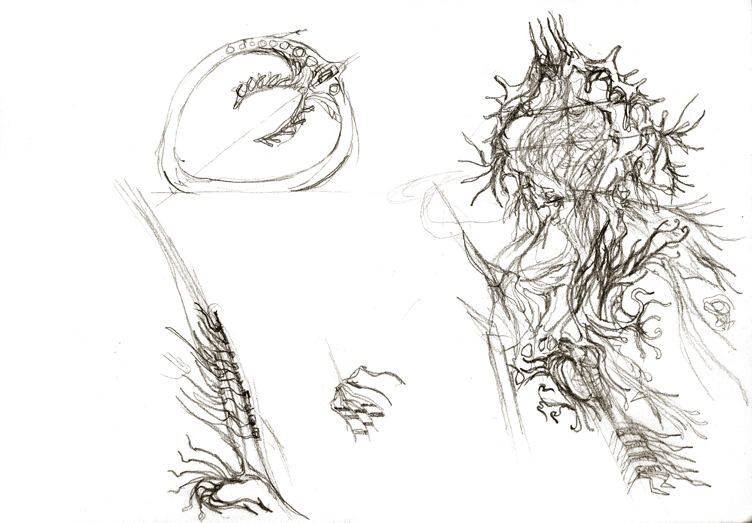

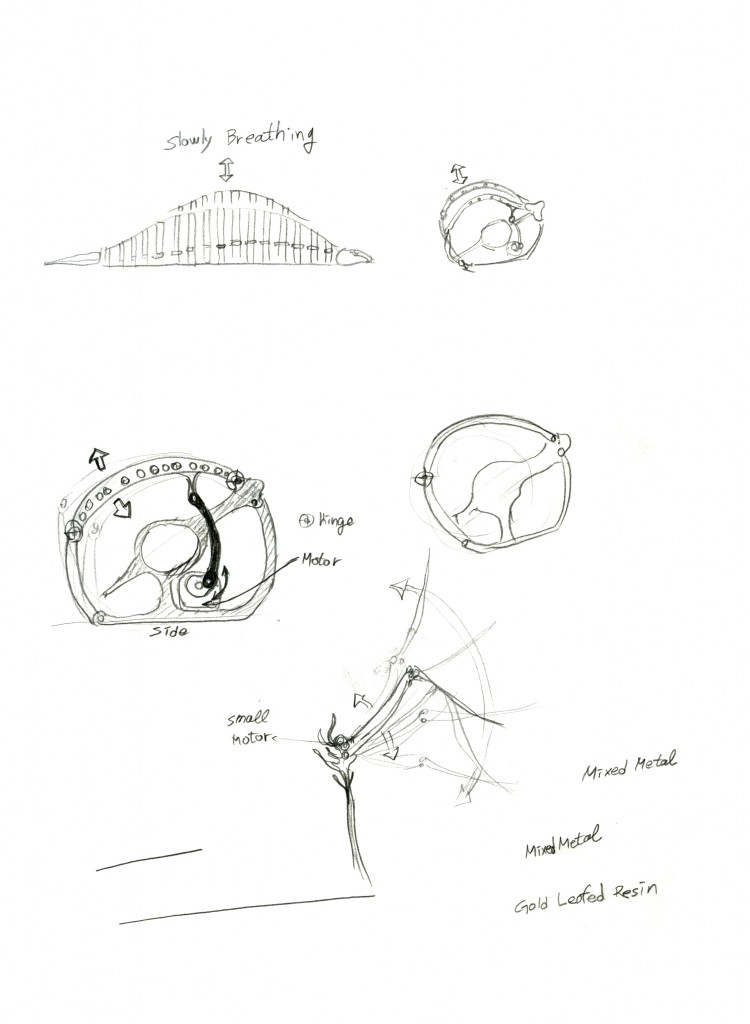

Untitled (drawing for Custos Cavum), 2011

Pencil on paper with CG re-touching

Original drawing: W. 23.0 x L. 30.5 cm

MT:

Your Custos Cavum myth indicates a strong concern for ecology and the fragile balance of nature as well as the coexistence of all beings. It works as a cautionary fable for us living in today’s world. Have you given much thought particularly to environmental issues?

UC:

When I first wrote it, I wanted to feel and express the cycle of life and the history of the universe. It was interesting to me that the metaphors in ancient mythologies could still apply to modern society. All I did was draft the story based on these interests of mine. I didn’t intend to reflect on any particular environmental issues. But, after I completed the story and read it over and over for revisions, I was quite interested because the story definitely had some environmental elements in it.

In retrospect, environmental issues must have been on my mind because of the flood of news on the subject, and personally, I have long been highly aware of the environment. Human beings live in a global ecosystem. And our existence is finite; our lives are momentary compared to the eons of history of the universe. In spite of this, the discussion of the environmental crisis is often based on an arrogant evaluation of the importance of the human species. It is as if mankind has the almighty power either to destroy everything or to return it to life as it wishes. In addition, the politicians, having lost their public enemies, have created a new demon out of the environmental crisis to make us live in a never-ending spiral of guilt. The news I watch often makes me think the carbon dioxide that I make may someday doom the fate of mankind. Of course, mankind is part of the environment that surrounds us and we are supposed to respect it and live in peace and harmony with it. This is very important. But propagating fear and guilt is not the way to achieve this harmonious coexistence.

U-Ram Choe

Una Lumino, Scientific name: Anmopispl avearium cirripedia Uram, 2008

Metal, motor, LED, custom CPU board, Polycarbonate

H. 520 x W. 430 x D. 430 cm

MT:

Just as your past creations are linked to mysterious evolutionary histories, you are linked to a mysterious entity called the “United Research of Anima-Machines,” shortened as U.R.A.M. Where and how does it still exist?

UC:

U.R.A.M. is an imaginary organization that I created to provide a sense of existence to the anima-machines that I “discovered.” In reality it is just my own studio—but if any of you want to join my quest for discoveries, you can be a member of U.R.A.M., too. While I am currently working on a project about mythic themes, the organization remains latent. Once I discover a new anima-machine, though, it is ready to resume activities at any moment.

The anima-machines cannot be seen when we look at cities through the eyes of reason. If instead we look at the city as a forest where the artificial and the natural coexist, we discover that there are more entities than just natural life-forms. When we take a look at the scenery of the city from the top of a building, the first things we notice are the lines of shiny, box-like “animals” marching toward their destinations, “butterflies” that blink with clockwork regularity, and metallic “birds” that soar through the sky with a loud noise . . . there is no doubt that all of the artificial entities in the system—and the system itself—are powered by human desire.

MT:

You have done some research on Asia Society’s John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection of traditional Asian art, and for your exhibition, you selected Shiva as Lord of Dance as your source of inspiration. Why did this sculpture appeal to you? What aspect of it most inspired you?

Shiva as Lord of the Dance (Shiva Nataraja)

India, Tamil Nadu; Chola period (880-1279), about 970. Copper alloy

H. 26 3/4 in. (67.9 cm)

Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection

1979.020

UC:

When I was choosing my inspiration, I wondered what form would represent the absolute, the universe. That was when I came across Shiva as Lord of Dance. As far as I know, Shiva is the god who rules all of the principles of the universe. And the god was sculpted as a dancing figure. Today, many scientists are tormenting themselves to find out the fundamental, underlying principles of the universe, but people of ancient times understood nature as a comprehensive environment through symbolism and beautiful, brilliant metaphors. And I thought that maybe what I am doing is attempting to understand the great artists who made the great principles of the universe dance.