Introduction

Court patronage of the ceramic industry in China resulted in objects of unparalleled aesthetic and technical sophistication that were prized in their time and are still sought after today. The Song emperor Huizong (reigned 1101–1126) appreciated elegantly formed stoneware vessels with a variety of sensuous glazes. In the fourteenth century, artisans in the city of Jingdezhen mastered the difficult technique of decorating porcelain with cobalt blue pigment. After an imperial porcelain factory was established there in 1402, the kilns in Jingdezhen produced ever purer white porcelain. The blue and white wares made during the Ming dynasty Xuande era (1426–1435), with their spacious designs on a snowy white base, are considered some of the finest ever produced. In the later Chenghua era (1465–1487), artisans perfected the delicate doucai technique, in which colorful enamels embellished porcelain painted with underglaze cobalt blue.

From the Song dynasty onward, the production and possession of fine ceramics became increasingly important symbols of cultural sophistication and power. Technical innovation at Jingdezhen was driven, in part, by a desire to emulate and surpass the achievements of the past. In the Qing dynasty, for example, the intricate, naturalistic scenes on the porcelain of the Yongzheng era (1723–1735) represent an effort by the emperor to outshine the Xuande and Chenghua wares of the earlier Ming dynasty. The significance of imperial ceramics persists; newly prosperous collectors in China today vie to own these compelling examples of their country’s artistic achievement and courtly magnificence.

China’s peerless ceramics have been treasured for centuries not just at home, but around the world. Early porcelain from Jingdezhen was a rare luxury in the royal courts of the Middle East, Mughal India, and early modern Europe. Beginning in the sixteenth century, export porcelain of a lesser quality gradually became a more widely available commodity. However, as contact between China and the West increased in the mid-nineteenth century, collectors gained new access to, and a keen appreciation for, the much finer vessels beloved by Chinese connoisseurs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd was among the prominent Americans who sought out imperial wares in the twentieth century. For nearly one millennium in China, teams of skilled workers, precious materials, and strict official supervision were devoted to producing ceramics to please the emperor; it is no wonder that these pristine objects continue to hold great appeal for viewers and collectors around the world.

Lara Netting

Guest Curator

Brush washer. Henan Province. Northern Song period (960–1127), early 12th century. Stoneware with glaze (Jun ware) Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.138

This elegant brush washer with a ring handle exemplifies the court taste that developed under the patronage of the Song emperor Huizong (reigned 1101–1125). Rather than any painted or incised motifs, the only surface decoration is the very thick, blue-gray glaze. This type of ware, known as Jun ware, was available to a broad range of people. Ever since the Southern Song dynasty (1132–1279), however, Jun ware has been appreciated by connoisseurs as one of the “five great wares” of China.

The flattened gourd shape of this bottle derives from metalwork and ceramic flasks of Iranian, Syrian, or Turkish origins. The stylized lotus medallion lightly incised in the center of the bottle, with its geometric quality, also reflects renewed interest in the Middle East. In the late fourteenth century, warfare associated with the establishment of the Ming dynasty had slowed the worldwide export of Chinese ceramics. The trade was officially reopened in the Yongle period (1403–1424), and the form and decoration of ceramics from the early fifteenth century show the impact of foreign markets.

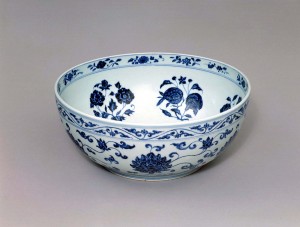

Bowl. Jiangxi Province. Ming period (1368–1644), early 15th century (probably Xuande era, 1426–1435). Porcelain painted with underglaze cobalt blue (Jingdezhen ware). Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.169

The blue and white wares of the early fifteenth century are considered exceptionally beautiful, and this impressive bowl captures Chinese imperial taste of that time. The scrolling lotus vines and camellias, litchis, peaches, pomegranates, peonies, and chrysanthemums create a pleasingly balanced design in cobalt blue, carefully depicted within expanses of white background. Xuande-era potters had succeeded in removing nearly all impurities from the clay, and this open composition showcases their achievement.

Bottle. Jiangxi Province. Qing period (1644–1911), Yongzheng era, 1723–1735. Porcelain painted with overglaze enamels (Jingdezhen ware). Asia Society, New York: Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.189

The lush decoration on this bottle features bright yellow loquats, red-orange pomegranates, and pale green peaches with a blush of pink. These varied colors were only made possible by the development of opaque enamels at Jingdezhen during the early eighteenth century. Unlike the earlier transparent enamels, the opaque colors could be blended together to create a wide range of shades and hues. Porcelains displaying the new palette were extremely popular in Europe and they were classified with the French name famille rose. A six-character Yongzheng reign mark appears on the base of this bottle.

Share

Share