|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HOME > ESSAYS > Introduction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

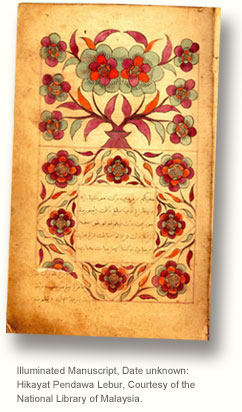

Introductionby Morris RossabiThis curricular guide, intended for use by teachers in high schools and of introductory college courses, is one of several Asia Society projects designed to foster the study of Islamic communities in Asia east of Iraq as an important and little-studied part of Asia in history and today. The Education division at the Asia Society has originated these programs not only as part of its general mission to educate Americans about Asia, but also in response to educators’ requests for materials about the history, land, peoples, beliefs and cultures of the majority Muslim areas of Asia, which tend to be poorly resourced and infrequently studied at all levels of American education. Southeast Asia is a region that has received limited attention in the U.S. secondary school curriculum. Other than descriptions of the Vietnam War and its aftermath (including sometimes the massacres in Cambodia), a brief listing of the colonial countries and their colonies, and perhaps a reference to Anna and the King of Siam, the secondary school curriculum barely touches upon either mainland or island Southeast Asia. Moreover, as far as we have been able to ascertain, no comprehensive set of units on the region’s geography, history, arts and literature, religions, and social patterns for American high school students has been produced. Features of its unique environment, its cultural heritage (particularly the shadow puppet, or wayang, tradition), and its social organization are occasionally incorporated in general courses or units on geography, world history or art, but few, if any, comprehensive curricular projects on Southeast Asia have appeared. This omission may seem puzzling, particularly in the case of Indonesia, the nation with the fourth largest population, and the largest Muslim population, in the world. Part of the explanation lies in the limited nature of the contacts between the U.S. and most of the region before World War Two. The Netherlands, Portugal, France, and Great Britain had established colonies in Indonesia, East Timor, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Burma, Singapore, and Malaysia. The U.S. was not dominant in Southeast Asia except

in the Philippines, which it wrested from Spanish

control in 1898. Scant political or economic relations

translated into general lack of U.S. interest and knowledge

about the region. Southeast Asia’s complexity and

diversity may also have precluded its inclusion in the

secondary school curriculum. As the essays in this volume

attest, in pre-modern times Indian, Arab, Persian,

and Chinese civilizations influenced Southeast Asia’s

history, religions, literature, economies and arts. Many

American teachers themselves have not had the training

on the region itself, nor of these critical cultural influences,

to allow them to feel comfortable teaching the

material. In addition, it is challenging even to find a basic

context for teaching the region when their students

generally lack the requisite background knowledge

of these other civilizations, as well as of key cultural

manifestations, for example, the Ramayana and Arab

and Persian tales, that would allow them to appreciate

Southeast Asia’s cultural richness and provide them with

some natural entry points into the study of the region.

As poor as most American students’ general knowledge about the rest of the world--including Asia--is [1], students’

global vocabulary today tends to include at least a few

references for China, Japan and India, but very few for

the “lands below the winds,” despite their importance

for the history of trade, for examples of post-colonial

development, and for crucial understandings of the Seeking to overcome these problems, this curricular guide focuses on Islam in Southeast Asia rather than on an all-inclusive introduction (which is why, after the general introduction to the region provided by Barbara Watson Andaya’s essay, the guide focuses on regions and countries where Islam is the majority religion, and does not include sections on the region’s many Muslim minority populations, such as the Rohingya of Burma or the Cham of Cambodia.) Even so, this emphasis is fraught with difficulties in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon in September 2001. Speculation in the some media outlets and in popular discourse (for example, in chat-rooms and internet discussion sites, letters to the editor, radio call-in shows) about a clash of cultures between the Muslim world and the West, or, worse, wide-spread stereotypes about tendencies to violence among Muslim peoples, impede American students’ unbiased consideration of the role of Islam or go so far as to instill fear into many members of the American public of everything associated with Islam. This curricular effort seeks to respond to the long-term political dangers inherent in wide-spread ignorance about Islam in its many manifestations around the world, through introducing students to Islam as it is lived and practiced in a part of the world many associate much less with Islam than they do the Middle East. The creation of these materials also seeks to remedy the situation described in an article entitled “Teaching Islam in Southeast Asia”: scholar and educator Nelly van Doorn-Harder points out that “[the] frustrating part [of trying to promote the teaching of Islam in Southeast Asia] is the paucity of material suitable for the level of high school and college students.” [2] The guide offers a thematic presentation of Islam in Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia specialists have written four background essays and several mini-essays and created a detailed time-line on the most important aspects of the region’s human geography, culture, and history, selected primary and secondary sources on the topics they address, and have provided illustrations and guides to additional reading. A group of teachers and curriculum experts has then devised sample lesson plans based upon the written materials and illustrations offered by the scholars. A cartographer created maps especially for the project, also based on suggestions made by Academic Advisors. Remarkable diversity is the principal characteristic to emerge from these essays. Barbara Watson Andaya writes that of the six thousand spoken languages in the contemporary world, about one thousand may be found in Southeast Asia, a graphic illustration of the differences in the region. The maps she has suggested creating considerable ethnic diversity, while the photographs she selected show differences in lifestyle. Such diversity may be due partly to Southeast Asian geography. The remoteness of the highlands on the mainland and the sheer number of islands that make up Indonesia have helped local people to retain their distinctive cultural identities. In addition, external influences and their acceptance and assimilation by different Southeast Asian groups have contributed to considerable diversity. Indian, Chinese, Islamic, and Western cultures have all reached Southeast Asia in different periods and forms and to different regions and peoples. These influences, on occasion, have blended together to produce hybrid cultural manifestations. The Indonesian wooden and shadow puppet theaters, for example, sometimes combine Islamic and Indian traditions of story-telling. This diversity has spilled over into the practice of Islam. Religious observances differ in various Southeast Asian communities. These variations challenge the often stereotypical ideas about the lack of flexibility in Islam. The different ways in which Islam was introduced into Southeast Asia no doubt contributed to such diversity. Chinese, Indian, Persian, and Arab merchants each brought their own versions of the Islamic message, and Southeast Asians themselves traveled to West and South Asia to study the Qur’an and the hadith with prominent teachers in these regions. Differing exposure to Islam resulted in considerable variation in religious forms and expressions. Islam’s adaptability also led to diversity. Its adoption of Hindu-Buddhist temple architecture in the design and construction of many mosques and its localization or acceptance of some earlier indigenous traditions added to the variety of forms of religious expressions. A common theme in all the essays is that, contrary to common Western stereotypes, Islam in modern Southeast Asia has not been monolithic. Differing views of Islam persist among different Muslim communities within Indonesia and Malaysia, the countries in Southeast Asia with the largest Muslim populations. The “Sisters in Islam” movement in Malaysia, for example, represents opposition to the conservative views of women’s positions in Islam, in society and in the home, and advocates greater rights for women, as well as a greater public role. Yet, as the “Sisters in Islam” movement acknowledges, the authority of men over women and covering of women’s bodies, for example, are still controversial issues within the Muslim community. No single view prevails about these issues. In short, the practice and observance of Islam in Southeast Asia are much more complex and nuanced than the conventional view among many in the Western world suggest. The regional specialists on Southeast Asia who wrote the thematic essays, the educators who devised the lesson plans, and the program directors and advisors, recognizing students’ different learning styles, have selected varied curricular materials. Secondary source materials emphasize the specific rather than the theoretical. Sections from literary works offer vignettes designed to encourage students to read more of these texts. A range of illustrations, from scenes of daily life in different parts of Southeast Asia to images of artistic works, enliven the text and can be used to build students’ visual literacy. The photographs are important teaching tools. They show different lifestyles, illustrate the mixture of indigenous, Indian, and West Asian designs in architecture and other art forms, and reveal the differing West and South Asian influences on Indonesian puppet theater. A variety of maps also yield insights about Southeast Asian topography, ethnic and language groupings, traditional trade patterns, and the spread of Islam. Teachers thus can use both written and visual materials to foster interest in and knowledge of Islam in Southeast Asia.

NOTES 1 For the state of U.S. students’ knowledge about the rest of the world

outside the U.S., including Asia, see the Asia Society/National

Commission on Asia in the Schools report, Asia in the Schools: Preparing

Young Americans for Today’s Interconnected World (2001) and the 2 Nelly van Doorn-Harder, “Teaching Islam in Southeast Asia”, in

Education about Asia 10:1 (Spring 2005), p. 14. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||