Excerpts from “The Fate of a Painting” by Shen Jiawei

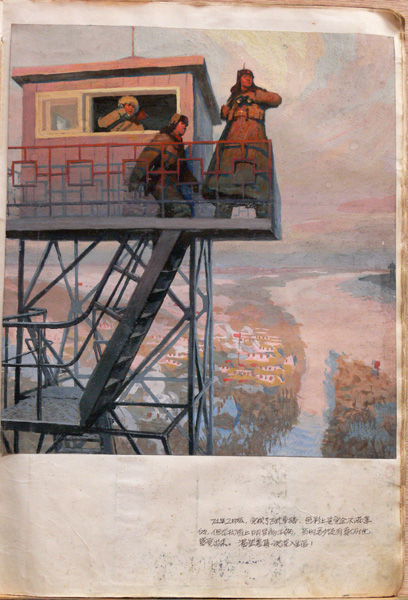

Since its completion in 1974, my oil painting Standing Guard for Our Great Motherland has had a very strange fate. It has become somewhat of a cultural artifact, an embodiment of the narrative of the Cultural Revolution.

When Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution in May 1966, it signaled the end of my dreams of studying at an art academy. But at the same time, the Cultural Revolution turned me into a painter, and, what is more, a painter who achieved fame at a very young age.

………………

I grew up in a small provincial city and never had the chance to be trained in the fundamentals of art. My only influence was an uncle who had studied art in the past. So, before I became a painter, I had never done life drawing, plaster modeling, or still lifes. In fact, many artists of my generation were able to become oil painters only because of the Cultural Revolution. Before 1966, most Chinese households could never have afforded to buy oil paints for their children who studied art; most people’s monthly salaries amounted to the cost of only a few dozen tubes of paint. But during the Cultural Revolution, all work units needed people to paint portraits of Mao Zedong. Once we completed the paintings, we were allowed to keep the leftover paints to do our own work. This is why oil painting (western painting) subsequently became so widespread in China; it was one of the more positive by-products of the Cultural Revolution.

……………………

I completed my work [Standing Guard] in July 1974. In keeping with the practice of the times, I did not sign the painting, but wrote only my name and work unit on the back of the canvas. In September, I was notified that this work had been selected for the national art exhibition. In October, I went on leave and used my own money to travel to Beijing to see the exhibition. On the train, I used my scrapbook of source material to write and copy notes on the process I followed in creating the painting. These notes were half true and half fabricated. This was because at that time any kind of writing, even personal diaries, could be subjected to public reading. Any politically incorrect word could bring disaster in its wake. So I had to make sure that even my notes on my creative process were in keeping with official standards.

When I [arrived in Beijing and] walked into the National Art Gallery, I discovered that my painting was hanging in the most prominent position in the exhibition hall, on the center left. But when I moved in for a closer look, I was in for a shock: the faces of the two soldiers had been reworked. It was obvious that my efforts to paint a picture as close to reality as possible had not been acceptable to the authorities.

……………………………….

In 1981, a friend in the Heilongjiang Provincial Artists Association in Harbin told me that Standing Guard had been sent back by the National Art Gallery and was being kept in the art association’s storage area. He said that I could go and pick it up. The next year, when I went to get it, I discovered that both the outer and inner frames were gone. The canvas has been improperly rolled (outside in) and tossed into a rubbish heap in the basement. I unrolled it just a bit and saw that flakes of paint were coming off. When I got it back to Shenyang, I did not dare to open it all the way and just stuck it under my bed, where it stayed for many years.

In 1989, I emigrated to Australia. In 1997, I was invited by the Guggenheim Museum to lend it my painting for a major exhibition, “China: Five Thousand Years.” I asked someone to bring the rolled-up painting from China to Sydney for me. I took it to the conservation department of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and there, for the first time, I unrolled it completely. Everyone in the room at that moment was in shock: the painting was covered with soot and had suffered water damage; two-thirds of its surface had come off. Under the guidance of the professional conservators [there], I slowly and painstakingly restored the painting. However, there were two sections of the painting that I was glad were damaged: the two faces that had been repainted on the orders of Wang Mantian were completely obliterated. Referring to photographs I had of the original work, as well as my extensive notes, I was now able to restore them to their original appearance.

Translated by Valerie C. Doran

The full essay is printed in the exhibition catalogue, Art and China’s Revolution, available at AsiaStore.

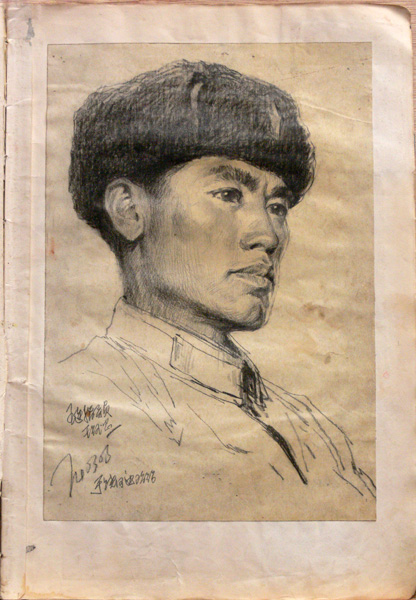

Drawing portrait of Private Wang Shu-ja, March 5, 1974. Charcoal on paper, 15 5/16 x 10 5/8 in. (39 x 27 cm)

Collection of Shen Jiawei

Drawing portrait of Company Director Wang De-zhong, March 5, 1974. Charcoal on paper, 12 3/8 x 8 1/2 in. (31.5 x 21.5 cm)

Collection of Shen Jiawei

The first composition sketch for Standing Guard for Our Great Motherland, December 15, 1973 (original caption written October 1974). Charcoal on paper, 10 1/4 x 7 1/8 in. (26 x 18 cm)

Collection of Shen Jiawei

Study for Standing Guard for Our Great Motherland, February, 1974. Charcoal and color on paper, 11 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. (28.5 x 26 cm)

Collection of Shen Jiawei