Chinese Imperial Taste and Beyond China

During the Song dynasty (960–1279), when collectors first acquired ceramics as art objects, a number of Chinese emperors were highly influential. Huizong, the Northern Song-dynasty emperor who reigned from 1101 to 1126, was the epitome of the Chinese emperor-aesthete, and his taste had a strong and long-lasting impact on the arts, ranging from poetry to jade carving. Under his patronage, new types of court ceramics developed. Unlike earlier Northern Song emperors, Huizong was not interested in the style of Ding ware, with its light colored and often imperfect glazes and incised and impressed decoration. Rather, the ceramics he was drawn to possess elegant forms and refined and sensuous glazes. From the time the Ming-dynasty emperor Jianwen (reigned 1399–1402) established the imperial porcelain factory at Jingdezhen in 1402, Chinese emperors found the translucent white porcelain body and its decorative possibilities irresistible. A masterful white ewer with delicately incised designs epitomizes the taste of the Yongle emperor (reigned 1403–1424), and bowls with underglaze cobalt blue floral designs produced under the Chenghua emperor (reigned 1465–1487) show a level of delicacy and perfection never before equaled. A number of Qing-dynasty emperors were distinguished for both encouraging innovations in porcelain decoration (at Jingdezhen and in imperial workshops at the capital) and collecting ceramics. One such figure is the Yongzheng emperor (reigned 1723–1735), under whose reign we find the perfection of sophisticated colors such as shades of pink in the overglaze enamel palette.

|

| Bowl

China, Jiangxi Province

Ming period, 1368–1644, early 15th century (probably Xuande era, 1426–1435)

Porcelain painted with underglaze cobalt blue (Jingdezhen ware)

The form and decoration on this impressive bowl capture Chinese imperial taste of the early fifteenth century. Carefully depicted within expanses of white background, the cobalt blue scrolling lotus vines and camellias, litchis, peaches, pomegranates, peonies, and chrysanthemums create a pleasingly balanced design. Chinese imperial patronage of blue and white porcelain began during the fourteenth century under the Yuan dynasty’s Mongol rulers.

|

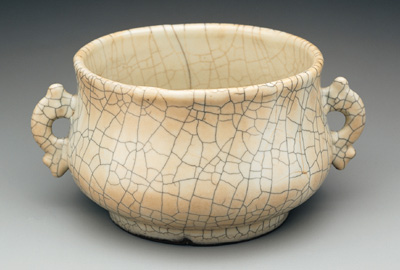

Censer

China, Zhejiang Province

Southern Song period (1127–1279), late 12th–early 13 th century

Stoneware with glaze (Ge ware) The delicate gray-green color of the glaze on this piece shows the influence of the earlier Northern Song imperial taste that carried into the preferences of the Southern Song court. This censer takes its form from the shape of a Western Zhou-dynasty (ca. 1050–771 B.C.E.) ritual food vessel called a gui, reflecting the impact of Southern Song period interest in antiquarianism among literati. Song period emperors, most notably Huizong, adopted cultured tastes of these educated elite and popularized them at court. |

|

|

Brush washer

China, Henan Province; Northern Song period (960–1127), early 12th century

Stoneware with glaze (Jun ware)

The elegant form and sensuous glaze of this small brush washer with a ring handle exemplifies the court taste that developed in the early 12th century under the patronage of the Song emperor Huizong (reigned 1101–1125). Jun ware is closely tied to Ru ware, a highly valued imperial ware produced in small quantities, which has been discovered at the same kiln sites that produced Jun ware.

| |

|

Bowl

China, Henan Province; Northern Song period (960–1127),

12th century

Stoneware with glaze with suffusions

from copper filings (Jun ware).

The quality of Jun ware varies enormously because it was produced in great quantity over a long period of time. Although Jun ware was clearly available to a broad range of people, it has traditionally been appreciated in China as one of the five great wares of China and has been classified along with Ru and Ding ware as one of the famous court wares of the Northern Song dynasty. The bright purple splashes in the glaze on this small bowl are characteristic features of Jun ware.

|

|

|

Bowl

China, Hebei Province; Northern Song period (960–1127),

11th–early 12th century

Porcelain with incised design under glaze, the rim bound with copper (Ding ware).

Highly refined Ding ware was among those ceramics that were presented to the Northern Song court. During the late Northern Song period Ding ware was fired upside down to prevent warping. Some scholars have suggested the unglazed rims, which were a result of this process, were unsuitable for imperial use and that the ware ultimately fell out of imperial favor for this reason. A copper band was fitted to the mouth of this bowl to make it more appealing visually and tactilely.

|

Leaf-shaped cup

China, Zhejiang Province; Southern Song (1127–1279)

to Yuan (1279–1368) period (1127–1368), 13th century

Stoneware with glaze (Longquan ware).

The organic shape, elegant grayish green glaze, and crazing of this unusual leaf-shaped cup illustrate the existence of close ties between some of the Longquan kilns, located not far from the Southern Song capital at Lin’an (now called Hangzhou), and the bluish-green glazed Guan ware produced for the Southern Song court.

|

|

|

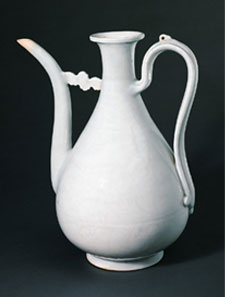

Ewer

China, Jiangxi Province; Ming period (1368–1644), early 15th century (probably Yongle era, 1403–1424)

Porcelain with incised design under glaze.

The Yongle era is famed for the smooth, white glaze seen on this ewer. The Yongle emperor, the third emperor of the Ming dynasty, took such pride in this white glazed porcelain that he even erected a white porcelain brick-faced pagoda at Nanjing. This pear-shaped ewer derives its shape from Middle Eastern metalwork. The innovative combination of an exotic foreign shape with Chinese designs suggests the two-way influences of the Chinese ceramic trade from the fourteenth to the fifteenth century.

|

Dish

China, Jiangxi Province; Ming period (1368–1644), early 15th century (probably Yongle era, 1403–1424)

Porcelain with incised design under glaze (Jingdezhen ware).

Two “hidden decoration” (anhua) dragons among three clouds are incised under the glaze in the interior of this thin dish. This technique was very popular in the early Ming period, at least in part because of the Yongle emperor's (reigned 1403–1424) taste for plain white wares. Dishes of this type, noticeably thinner than the majority of porcelains produced during the reign of Yongle, are known as eggshell porcelain. |

|

| Foliate dish

China, Jiangxi Province;

Ming period (1368–1644), early 15th century (probably Yongle era, 1403–1424)

Porcelain with incised design under glaze (Jingdezhen ware).

Excavations at imperial kilns have determined that porcelain covered with a warm white glaze were among the most popular ceramics produced during the reign of the Yongle emperor. Difficult to see at first glance, the extremely delicate incised pattern of grapes, flowers, and clouds on this small dish is the type often termed “hidden decoration” (anhua). Hidden decoration was very popular in the early Ming period, at least in part because of Yongle's taste for plain white wares. |

| Tea bowl

Fujian Province; Southern Song period (1127–1279), 12th–13th century

Stoneware with glaze with iron "hare's fur" and painted with overglaze iron brown slip, the rim bound with silver (Jian ware).

The Northern Song emperor Huizong (reigned 1101–1125) was a lover of the dried, powdered tea from Fujian, which was frothy white when whisked in hot water. This tea came from the same region where this Jian-ware tea bowl was produced. The emperor was also taken by Jian tea bowls, particularly those with “hare’s-fur” (tuhao wen) markings, as seen in the dark, thick glaze covering this bowl, which he said were the most desirable. This particular bowl postdates the reign of the emperor, but the unusual plum blossoms painted on top of the "hare's-fur" design suggest that it was produced for an important person. |

|

| More >> |

|